Sodium Nitrate: Substance, Science, and Society

Historical Development

Sodium nitrate has a legacy that weaves through agriculture, warfare, and the rise of modern chemistry. In the deserts of Chile, miners dug up vast beds of caliche—earth loaded with this salt—and shipped it worldwide. Farmers once depended on it as a key fertilizer, calling it Chile saltpeter, before the development of the Haber-Bosch process changed everything. The synthetic production of ammonia suddenly meant industry didn’t rely solely on South American sources. Wars in the early twentieth century drew heavily on sodium nitrate for explosives. During the nitrate boom, entire towns cropped up, built and abandoned at the whim of global demand. The industry left its mark on international trade, and even shaped environmental policy when people started to see how nitrate run-off from fertilizers polluted water sources.

Product Overview

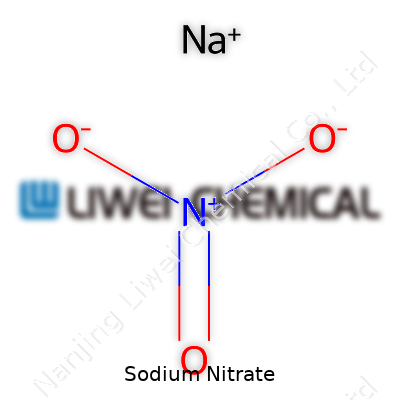

Sodium nitrate runs as a white, odorless crystalline powder. Folk see it labeled in gardening stores, chemistry labs, and in some food preservation processes. Chemically speaking, it’s straightforward: NaNO3, a simple inorganic salt. Producers supply it in bags or bulk containers, and some companies apply special coatings or anti-caking agents to help it pour cleanly. Every factory batch ends up with batch numbers, purity ratings, and instructions for safe storage and handling. Standards often push for a purity of 99% or higher. You see sodium nitrate in food-grade, technical-grade, or agricultural-grade varieties.

Physical & Chemical Properties

On the benchtop, sodium nitrate looks like everyday table salt, but when you look closer, differences stand out. At room temperature, it forms colorless or white crystals, readily dissolving in water—much more so than common salt. It melts at 308°C and decomposes at higher temperatures, releasing nitrogen oxides. It doesn’t catch fire by itself, but it encourages combustion by supplying oxygen. Its oxidizing properties attract attention from chemists and pyrotechnicians alike. If you taste it (not a good idea), you’d find it slightly salty and bitter.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Manufacturers assign sodium nitrate a CAS number: 7631-99-4. Packaging comes with hazard pictograms and warnings about oxidizer risks. Purity, moisture content, and particle size show up in technical sheets. European suppliers follow REACH regulations, while US producers look to OSHA and EPA standards. Labeling needs to disclose net weight, lot code, manufacturing date, and expiry period. The United Nations ranks it as a hazardous material under code 1498, restricting how shippers move it by land or sea, especially in large quantities.

Preparation Method

People often produce sodium nitrate on an industrial scale by neutralizing sodium carbonate (soda ash) with nitric acid. In this process, workers combine the raw chemicals in controlled reactors, extracting the product as the water evaporates—leaving behind pure crystals. Before synthetic methods, factories leached sodium nitrate from natural deposits, purifying the leachate by repeated cooling and crystallization. This original mining method ruled until cheap artificial production made it obsolete outside a few localities.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Chemists turn to sodium nitrate as an oxidizing agent. It reacts with organic material and many metals, releasing nitrogen dioxide or nitric oxide. Mixing it with sulfuric acid frees up nitric acid while leaving sodium sulfate. In fireworks, sodium nitrate acts as a fuel for colored flames. Composters even use it under controlled settings to manage decay. These properties fuel ongoing research into safer or greener oxidizing agents for industrial processes. Lab workers sometimes substitute sodium nitrate for potassium nitrate in certain reactions, though differences in solubility and ionic size make substitution far from simple in every case.

Synonyms & Product Names

Sodium nitrate carries a long list of alternative names. Call it Chile saltpeter, soda niter, or nitric acid, sodium salt. On food ingredient labels, watch for E251. Chemical supply catalogs might mention Peru saltpeter, Soda nitratum, or cubic nitre. In the explosives trade, 'nitrate of soda' refers to this same compound.

Safety & Operational Standards

Sodium nitrate does not ignite materials by itself, but people worry about its role as a powerful oxidizer. If stored with organic substances or in a damp warehouse, it increases fire risk. Workers need gloves, goggles, and dust masks when handling the pure compound. Safety data sheets call for storage in cool, dry, and well-ventilated places. Regulators tell factories to avoid spills near bodies of water because runoff can cause eutrophication and harm aquatic life. Food applications face extra scrutiny, with strict residue limits and labeling laws. For large sites, national regulations pretty much always require training on emergency response and environmental management.

Application Area

Sodium nitrate left a footprint in fields, kitchens, laboratories, and factories. Agriculture once absorbed most of the world’s output, feeding a hungry planet through decades of fertilizer use. Gardeners add it to certain plant feeds, especially for leafy crops. Meat processors use it as a preservative, slowing bacterial growth and preserving reddish color in sausages or cured ham, though public health agencies increasingly watch nitrate levels in food. Pyrotechnicians depend on sodium nitrate for fireworks, fuses, and some explosives. Environmental labs run tests for nitrate concentrations in soil and water samples, keeping tabs on potential pollution sources. Even today, certain glass and enamel recipes call for sodium nitrate because of its ability to produce intense colors and stable glazes.

Research & Development

Research into sodium nitrate never really slows down. Projects target improved production routes that lower greenhouse gas emissions, safer storage techniques, and nitrate substitutes for sensitive industries. Some groups explore sodium nitrate as a phase change material in thermal energy storage—absorbing heat from the sun during the day and releasing it at night. Food scientists re-examine nitrate’s role, balancing its power as a preservative against growing health worries. Medical researchers look at nitrate’s metabolic pathways, hunting for links between dietary nitrate intake and cardiovascular health.

Toxicity Research

Toxicologists dig deep into how sodium nitrate affects cells, wildlife, and people. Swallowing moderate amounts links to short-term headaches, stomach pain, or dizziness. The bigger concern revolves around nitrate’s conversion to nitrite in the body and possible creation of carcinogenic nitrosamines, especially in preserved meats exposed to high heat. Water supplies contaminated with agricultural run-off raise alarms for infants, who become prone to “blue baby syndrome” because their blood can’t carry enough oxygen. Surveys of groundwater in farm regions highlight this ongoing risk, spurring new monitoring essentials. Animal studies track chronic exposure, mapping out potential harm to ecosystems where nitrate builds up over months or years.

Future Prospects

Sodium nitrate’s future runs through tight regulatory spaces, changing industrial demands, and new technologies. Farmers face restrictions and shifting recommendations over nitrate fertilizers. Wastewater managers search for ways to strip nitrates from effluent before it flows into rivers and lakes. The energy sector considers sodium nitrate for solar farms and large batteries, banking on its capacity to help store intermittent renewable energy. Public health scientists and food regulators re-evaluate acceptable daily limits. Green chemistry pioneers may introduce next-generation oxidizers, but sodium nitrate’s low price and ready availability keep it in the game. What holds constant is the push for safe management, environmental caution, and a steady lookout for smarter, healthier alternatives.

Sodium Nitrate at the Grocery Store

Anyone who’s ever read the back of a hot dog or bacon package might recognize sodium nitrate. Packaged meats often use it as a preservative so they can last longer on the shelf and look more appealing with that pink color. In the kitchen, the stuff helps keep cured meats from turning gray and spoiling too fast. Decades ago, people salted and smoked meat to keep it fresh, but sodium nitrate changed that with a quick sprinkle or soak.

Fertilizers and the Growing World

Walk onto a farm and you’ll hear about yield—how much corn or wheat a field can kick out each season. For those farmers, sodium nitrate plays a role in helping crops grow faster and stronger. Spread out on soil, it delivers nitrogen, an essential plant nutrient. Some fields produce more food, thanks to a chemical first mined in Chile long before mass food production. Countries facing starvation in the early 1900s counted on these fertilizers to help feed millions.

Booms, Busts, and Chemistry Class

Not everyone thinks about the role of sodium nitrate in fireworks or explosives, but it does its job there too. The same compound that keeps sausage pink can help propel rockets or set off a firework show on New Year’s Eve. It supplies oxygen in chemical reactions that make things go bang. In school chemistry labs, teachers lean on sodium nitrate because of its predictable reactions. It helps students learn how molecules split and bond.

Safety and Health Concerns

There’s a flip side to all this. Too much sodium nitrate in food adds to the risk of health problems, especially with regular consumption. Studies link high intake to certain cancers and high blood pressure. The World Health Organization classifies processed meats as a carcinogen, partly because of the nitrates they contain. Nobody wants to give up their favorite cold cuts, but it’s hard to ignore what researchers keep finding.

The compound poses risks outside the kitchen too. In water supply, high concentrations can lead to blue baby syndrome—this is when babies can’t get enough oxygen because of nitrate-contaminated water. Many rural communities run expensive tests and buy new treatment systems for clean, safe water, all because of fertilizer runoff from nearby fields.

Rethinking Our Relationship with Sodium Nitrate

So how do we balance the benefits and the risks? At the meat counter, some producers turn to celery powder or sea salt, which naturally contain nitrates but with less controversy. On the farm, precision agriculture technology helps put fertilizer only where it’s needed, cutting down on the runoff. Companies and researchers push for better water filters to protect vulnerable families. Public health campaigns teach folks to read labels and go easy on processed meats.

Sodium nitrate isn’t just a line in a chemistry textbook. It shapes what we eat, how fast our crops grow, whether a baby gets safe water, and even what lights up the sky at a festival. Most people don’t think about where it goes after leaving the store, but it leaves a trail worth following—one with real consequences and a need for smarter, safer solutions.

Why the Question Matters

Sodium nitrate pops up on labels for bacon, ham, jerky, and even hot dogs. Many people eat these foods at backyard cookouts, school lunches, or during a quick road stop. That pink, salty flavor stands out, and for decades, folks haven’t thought twice about it. Then stories began popping up about nitrates and health. Now, people wonder if a common sandwich ingredient could pose a threat.

Understanding Sodium Nitrate

Sodium nitrate comes from both nature and science. It exists in small amounts in certain vegetables, but food makers add it to deli meats and cured products. Its main job keeps meats pink and prevents botulism, an illness nobody wants to deal with. Nobody wants sandwich meat turning gray and slimy in three days, so sodium nitrate sticks around in grocery aisles everywhere.

Looking at the Risks

The big concern with sodium nitrate isn’t about the chemical itself. Problems mostly come later after it reacts inside the body or during cooking. In the gut and at high heat, it can change into nitrites and then into chemicals called nitrosamines. Some research links these nitrosamines to cancer, especially in the gut. The World Health Organization points toward processed meats as raising cancer risks over time, mostly because of these added chemicals.

Doctors and researchers have watched people who eat a lot of processed meats for years. Studies from large groups, like the EPIC study in Europe, noticed higher colon cancer rates among folks eating the most processed meat. The American Cancer Society cites research pointing in the same direction. Every few months, new data reminds us to take a closer look.

What Science Shows

Many foods naturally contain nitrates. Spinach, celery, and beets have more nitrates than that slice of bacon, but nobody worries as much about salad. Vegetables come packed with antioxidants, vitamin C, and fiber. These nutrients lower the odds of nitrosamines forming, so the body safely processes natural nitrate. The trouble occurs with cured meat, high heat, and low levels of protective nutrients.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration sets limits on how much sodium nitrate food makers can use. The law also requires adding vitamin C or similar compounds to lunchmeat to cut nitrosamine formation. That rule has a real impact. Tests show that nitrosamines in today’s cured meats have dropped compared to products from decades past. Still, the cancer connection hasn't disappeared completely, especially for those eating deli meats daily.

Balancing Enjoyment With Health

People shouldn’t panic at the sight of sliced turkey. An occasional hot dog at a baseball game doesn’t doom anyone’s future. My own family enjoyed homemade ham every holiday growing up, and most of us stayed healthy well into old age. The real issue comes from everyday habits. If sandwiches stacked with cured meats sit on the menu five times a week, the risks stack up too. Flavorful food brings joy, but health often comes down to moderation and variety.

What Can Help

To lower risk, focus on simple swaps. Substitute some processed meats for grilled chicken, roasted vegetables, or plant-based patties. Pick salads now and then instead of a loaded cold-cut sub. Try baking or steaming food instead of frying. Remember, vitamin C in fresh fruit or tomatoes with a meal can counteract some of the possible harm. Reading food labels for sodium nitrate or nitrite can help steer choices at the grocery store.

Long story short, sodium nitrate’s story comes with both benefits and downsides. Keeping cured meats as an occasional treat while stacking up veggies and fruits on the plate gives the body a fair shot at lasting health.

What Is Sodium Nitrate and Where Does It Show Up?

Walk into any grocery store and you’ll quickly spot those packages of bacon, lunch meats, sausages, and even certain cheeses claiming longer shelf life. Sodium nitrate keeps these foods from spoiling and helps them keep their color. It's been doing this job since long before many people were born. The additive stops the growth of bacteria that can make folks very sick, like Clostridium botulinum, which causes deadly botulism. Because processed meats have become a staple in many diets, sodium nitrate has become a regular part of the modern food landscape.

The Health Risks: Digging Into the Science

The risks tied to sodium nitrate don’t always show up right away. Scientists have spent years studying whether nitrate and its chemical cousin, nitrite, could hurt people down the line. The main worry centers on how these chemicals change once inside the body. In the stomach, nitrates can turn into nitrites, then sometimes change into nitrosamines—compounds scientists link to different types of cancer, especially colon and stomach cancer. The World Health Organization says eating processed meats, often packed with nitrates, can raise cancer risk. One large analysis published in the journal Cancer Medicine in 2015 found that people who ate more processed meats faced a higher risk of colorectal cancer than those who didn’t.

The problems don’t stop at cancer. High levels of dietary nitrates and nitrites have been connected to heart and blood vessel damage over time. There’s even a potential link with type 2 diabetes and increased risk for high blood pressure. In kids, nitrite exposure could trigger "blue baby syndrome," which affects how blood carries oxygen. Even small trace amounts add up if they show up regularly in meals.

How These Risks Affect Everyday Eating

Many families rely on convenience foods for packed lunches, picnics, and fast dinners after a long workday. As someone who grew up in a household that prized bologna sandwiches for a quick bite, I can honestly say I never gave much thought to what was keeping that meat pink and fresh. Cutting back on processed meats didn’t sound appealing until I saw stories about the cancer risks and read labels more closely. More folks are starting to notice, with experts pushing for whole, fresh foods that don’t need these chemical preservatives.

What Can Be Done?

One straightforward fix: swap out deli meats and hot dogs for options like roasted chicken, beans, or eggs. Busy parents might wonder how to get kids on board, but it helps to start slowly. Home-cooked leftovers, fresh fruit, and veggie snacks work in lunches and often save money in the long run. Grocery stores now offer more nitrate-free products than ever. Look for products labeled “no nitrates or nitrites added”—but be aware that some brands use celery juice or powder, which contain natural nitrates.

At a policy level, calls have gone out for tighter food regulation. The U.S. and Europe set maximum limits for nitrates in foods, but enforcement varies. Public health groups want clearer labeling, education campaigns, and support for schools to provide healthier food.

Limiting nitrate intake isn’t just about skipping bacon. It’s about paying attention, sharing food knowledge at home, and making swaps that help bodies thrive long term. Food habits change little by little, but every chance to swap that sandwich meat for something fresher means fewer risks over a lifetime.

Straight Talk on Why Storage Can’t Be an Afterthought

Sodium nitrate has quietly supported everything from fertilizer production to rocket launches. Walk into a plant that uses this stuff and you’ll notice the extra caution. I’ve spent time on agricultural sites, and there, labels for sodium nitrate don’t look like marketing—warnings are blunt. No room for mistakes, because sodium nitrate isn’t just another powder on the lab shelf. This chemical’s strong oxidizing power can speed up a fire faster than folks expect. Safety isn’t an abstract suggestion; it’s an everyday rule you can’t skirt.

Concrete Rules, Not Suggestions

People storing sodium nitrate rely on more than just a locked door. Dry, cool, well-ventilated areas matter. This chemical soaks up moisture like a sponge and forms lumps. In real-life storage, I’ve seen bags stacked on wooden pallets with plastic sheeting underneath to block leaks or drips. Nobody wants moisture mixing in because that opens the door to chemical reactions and slick floors, and it can corrode containers. No one likes dealing with a spill, but nothing beats shoveling up sticky nitrate soup surrounded by nervous workers. Every bag or container needs its own label—bold, clear, not half-covered in dust. People need to know what they’re handling, and there’s no prize for guessing wrong.

Mixing Sodium Nitrate: Playing with Fire

Sodium nitrate and flammable stuff never mix—a lesson driven home by more than a few close calls. I remember one small-town warehouse storing fertilizer next to barrels of oil. It didn’t take long before they got a stern visit from the fire inspector. Not just because of the law, but because you can’t trust luck with chemicals that can fuel an explosion. Warehouse staff took it seriously after that—separated the nitrate, used non-combustible building materials for the storage area, no exposed wood or insulation where a spark could hide. Even the smallest oversight—an oily rag tossed in by mistake—brings the risk right back.

Eyes, Skin, Lungs: Real People, Real Protection

A forklift driver, a warehouse hand, a junior chemist—all working near sodium nitrate need their own game plan. Gloves, goggles, and masks seem like overkill to a newcomer. Past experience tells me the sting of careless contact isn’t forgotten easily. Harsh powders like this can burn skin or cause eye injuries, and airborne dust leaves workers wheezing if they don’t wear masks. Emergency showers and eyewash stations stay ready, not as a box-ticking exercise, but because accidents don’t announce themselves before hitting. Training gets renewed regularly because rules drift out of memory after a few uneventful months.

Learning from Real Accidents—Not Headlines

Tragedies tied to poorly stored sodium nitrate don’t just fill newspaper columns. They reshape safety rules. After the Beirut port disaster, many countries reviewed what sat in their own warehouses. Local communities get anxious living near bulk stockpiles, and with good reason. Clear labeling, documented inspections, and strict no-smoking signs—these don’t replace good judgment, but they help keep a risky material from turning into a local headline.

Practical Solutions for Everyday Safety

Routine matters more than big gestures. I’ve seen the difference between a crew that sweeps a storage room daily and one that leaves heaps of broken pallets and spilled chemical. Clean workspaces lower the risk of slips, accidental mixes, and sneaky fires. Locking storage, limiting access, keeping chemicals logged—none of it sounds glamorous, yet each step builds a safer workplace. Reaching out for expert help during large projects beats making it up as you go along. All it takes is one overlooked routine check to create a chain reaction, and nobody wants to learn that the hard way.

Why Sodium Nitrate Gets Attention

Sodium nitrate pops up in all sorts of places: home-curing meat, science classrooms, even certain gardening projects. It sounds like just another powder, but the stakes can run higher than table salt. In my days dabbling with homemade jerky, finding a reliable source felt more complicated than picking up flour, and that's not by accident. This stuff has ties to food preservation, fireworks, and even old-school fertilizers. You don’t see it sitting on every pharmacy shelf for good reason.

Rules That Shape Where You Can Buy It

In the United States, sodium nitrate exists in a kind of gray zone because of its dual uses. Cooking enthusiasts want it for curing bacon and sausage. Teachers look for a pure sample for student experiments. People with green thumbs may notice it listed in fertilizer blends. The other side of the coin involves its use in explosives and pyrotechnics, which means sellers must tread carefully and buyers should expect questions along the way.

Years ago, I learned that many garden centers avoid pure forms of sodium nitrate. Regulations make it easy for stores to skip carrying it. Most big-box home stores stick to blends with much smaller concentrations. I can count on one hand the number of specialty garden suppliers carrying reasonably pure sodium nitrate, and I always see warnings about how sales get monitored.

Finding a Trustworthy Supplier

For anyone wanting sodium nitrate, the best bet starts with specialty retailers online. Companies focusing on meat curing supplies usually offer food-grade sodium nitrate, often labeled as “Prague Powder #1” or “#2,” blended for safety and consistency. These sellers back up their products with safety info and clear legal warnings. Pricing tends to land higher here, partly because regulation brings extra hurdles.

Science supply companies also list sodium nitrate—usually in smaller, well-labeled increments. Here, the buyer sometimes encounters hurdles like proof of educational use or age verification. I remember needing a business tax ID just to get a one-pound jar. Most stores will not ship bulk amounts to a residential address.

That’s not to say you won’t find sodium nitrate through other sources. Auction sites and peer-to-peer platforms often list it under broad categories. This tempting route skips safeguards consumers might otherwise expect. Stepping outside regulated channels increases the risk of getting contaminated or mislabeled product, and it’s clear from news stories and FDA warnings that unsafe potassium or sodium nitrate can lead to hospital trips.

Why Oversight Exists and What to Watch Out For

The bottom line—safety matters. Sodium nitrate looks harmless, but mishandled or misused, it can cause significant harm. Ammonia nitrate headlines might make the news more often, but history tells plenty of stories about sodium nitrate mishaps in both kitchens and classrooms. Tools like Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS) should help a buyer double-check handling steps. This is not a corner to cut.

Anyone shopping for sodium nitrate will help themselves by brushing up on local and federal rules. Shopfronts willing to explain legal restrictions and provide proper certificates show they understand E-E-A-T principles: expertise, experience, authority, and trustworthiness. If a website or store doesn’t seem legit—limited company details, no customer service line, no ingredient disclosures—it’s smart to walk away.

Regulated substances like sodium nitrate still serve important roles, but buyers and sellers each shoulder responsibility. Knowledge, paperwork, and clear communication make a difference. In my own experience, the extra effort to verify a source has always paid off with safe results and peace of mind.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Sodium nitrate |

| Other names |

Chile saltpeter

Sodium saltpeter Nitrate of soda Norwegian saltpeter |

| Pronunciation | /ˌsəʊ.di.əm ˈnaɪ.treɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 7631-99-4 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1206950 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:71207 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1355 |

| ChemSpider | 10106 |

| DrugBank | DB06789 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.007.071 |

| EC Number | 231-554-3 |

| Gmelin Reference | Gmelin Reference: 14202 |

| KEGG | C00286 |

| MeSH | D018474 |

| PubChem CID | 24268 |

| RTECS number | WH2625000 |

| UNII | 99ZV8MN8OA |

| UN number | UN1498 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | NaNO3 |

| Molar mass | 84.99 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline solid |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 2.26 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | 82.3 g/100 mL (0 °C) |

| log P | -3.7 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | -1.3 |

| Basicity (pKb) | pKb > 14 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | +26.0×10⁻⁶ |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.587 |

| Viscosity | 4.6 mPa·s (at 20 °C, 1 M aqueous solution) |

| Dipole moment | 0 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 116.5 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | −467.85 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -467.7 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | V03AB21 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Oxidizing, may intensify fire; harmful if swallowed; causes serious eye irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS09 |

| Pictograms | GHS03,GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H272, H319 |

| Precautionary statements | P210, P220, P221, P264, P280, P301+P312, P305+P351+P338, P306+P360, P370+P378, P403+P233, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | Health: 2, Flammability: 0, Instability: 0, Special: OX |

| Autoignition temperature | > 600 °C (1112 °F) |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 Oral Rat 1267 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | 3750 mg/kg (oral, rat) |

| NIOSH | WW4250000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL: 15 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 30 mg/L |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | 300 mg/m3 |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Sodium nitrite

Potassium nitrate Ammonium nitrate Calcium nitrate Sodium sulfate |